Sousa Jamba | Jimmy Cliff’s African Legacy

Loading article...

There was, in the life of Jimmy Cliff, the Jamaican now at rest, a quiet marvel: perhaps he never suspected how deeply his voice penetrated anonymous lives across the world, including my own. For many of us, he wasn’t just a distant artiste; he was a spiritual kinsman who said what we couldn’t formulate, as if the music arrived first and consciousness followed behind.

I discovered Jimmy Cliff in 1976, when my family fled Angola for Zambia. Suddenly, I found myself in a world saturated with sound. In neighboring Zaire, Franco (the popular Congolese musician) reigned supreme and people still talked about the Ali–Foreman fight; the streets displayed platform shoes and bell-bottom trousers. On every corner, a radio crackled; the miracle was the portable record player, battery-powered, that spun worn vinyl and brought distant voices into refugee homes.

In the neighborhood where we lived, the most beloved album was the 1974 ‘House of Exile’ by Jimmy Cliff. The title track lodged itself in the spirit of a ten-year-old boy who could barely decipher English, speaking of the pain of exile and of a man who had scorned warnings and now walked within his own consequences. I didn’t grasp that entire moral; I clung to the word exile, repeated like a refrain, and the simple sensation of being far from Angola and my parents, while the adults prayed for return.

We followed the Angolan war by radio, jumping from station to station, not knowing where on the map the rest of the family might be. When ‘House of Exile’ played, the melody concentrated all the anxiety of that boy who went to bed not knowing on what earth his loved ones slept; Jimmy Cliff’s voice gave shape to a helplessness still without a name.

Another album marked me with equal force: ‘Follow My Mind’, from 1976, luminous and gentle. There were ‘Mama Look at the Mountain’, with its rising peaks, ‘No Woman, No Cry’, inherited from Bob Marley, and ‘You Are the Only One’, laden with tenderness. I thought of my mother, imagined a future wife, watched adults dance in embrace and sensed, without knowing how to say it, that human love and a silent trust in God mingled there.

Another song guided our crossing: ‘Many Rivers to Cross’. The image of successive rivers transformed life into an endless march. The melody spoke of the harshness of the path and the stubborn will to continue even when strength runs out. For those who had crossed borders, from camp to camp, those imaginary rivers merged with real trails and nights on borrowed ground. It became an intimate hymn to perseverance: one more step, one more river, one more day wrested from despair.

In 1978 came ‘Meeting in Africa’, which I listened to as one discovers a hidden continent within another. There was a track with a calypso flavour, reggae foundation and almost disco shimmer, Caribbean and yet African in its choruses and swing. In Lusaka, the music spread through radios and streets, poured from houses and buses; we received it as an invitation to reunion with brothers across the sea.

ONE FAMILY BENEATH THE SAME SKY

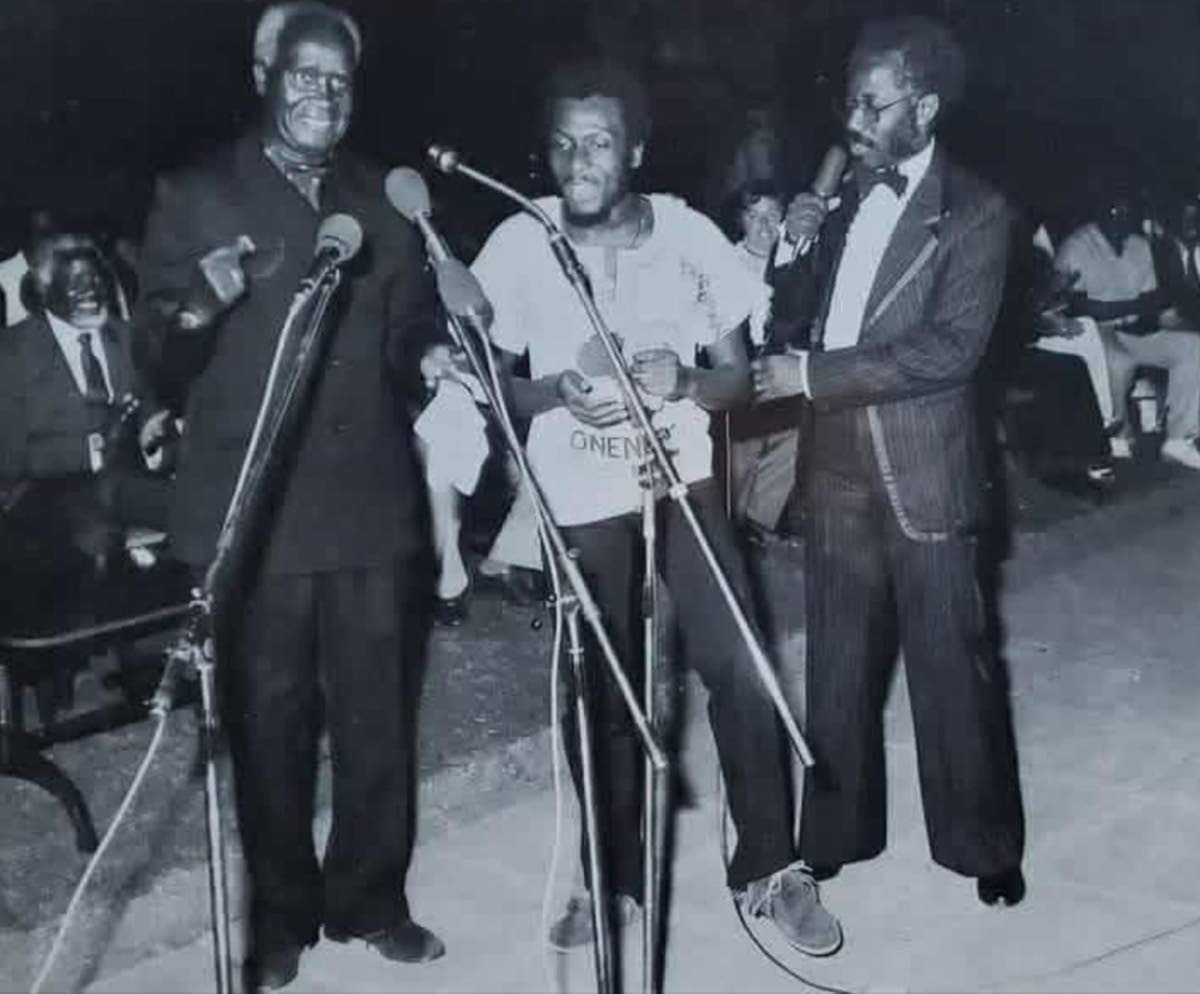

In 1982, Jimmy Cliff came to Lusaka in person. The airport was packed; when he appeared, they hoisted him onto shoulders like a returning king. The concert, at Independence Stadium, was the first of my life. I was sixteen, alone in the stands, and finally saw the man whose voice had accompanied my childhood.

He entered kicking a football; the stadium erupted when ‘Bongo Man’ began and the entire crowd sang, some weeping.

I was struck by the physical resemblance: Jimmy Cliff and the Jamaican musicians looked so much like us that, without the accent, they’d be taken for Zambians. That night, Africans from the continent and the diaspora gathered as one family beneath the same sky. Even the policemen, sent to keep order, had glistening eyes; for a few hours the stadium became a portable temple where everyone, unknowingly, knelt.

Only later did I grasp the harsh poetry of ‘No Woman, No Cry’, with its government yard in Trench Town where the poor crowded together. I recognised our condition there: we too were displaced, examined with suspicion in each new camp. When Jimmy Cliff sang, he seemed to address African refugees; the poor of Trench Town were our brothers in exile, and their tender, resistant lament said what my child’s heart already knew but didn’t yet dare confess.

Today I see Jimmy Cliff as a musician of tireless labor, rising from humble Somerton to reach the multitudes of Africa and the world. He left a trail of melodies that served as shelter for many of us. Decades later, his voice continues to inhabit my founding memories: exile, faith, first fantasies of love, rivers to cross, reunions between Africa and diaspora, the stubborn desire to return home.

May he rest in peace; the work he made suffices for many lifetimes.

- Sousa Jamba is an Angolan Writer and Journalist; and Former Communications Specialist at the Secretariat of the Organization of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS). This version of the article is translated from Portuguese. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com