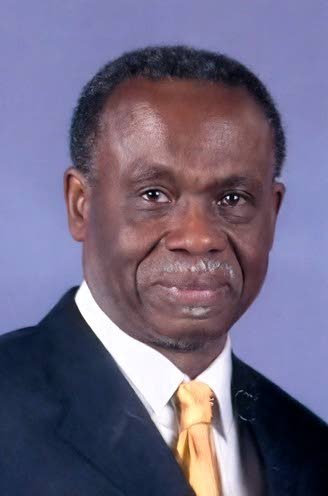

Lloyd Barnett | Impeachment: yes or no?

Loading article...

In the two previous articles in this series I dealt with cases in which the failure of members of parliament to perform their duties and discharge their responsibilities is in question and examined proposals for calling such members to account, including recall and censorship. Apart from non-performance, a member may commit reprehensible acts that are deserving of sanctions.

It is in this connection that the issue of impeachment arises and has become the subject of extensive debate. Any decision to adopt such a far-reaching system demands careful consideration of its historical record and the evidence relating to its fairness and efficiency.

Impeachment proceedings were adopted from Germany by England in the 14th century but fell out of use. It was reintroduced in the 17th century for a short time, after which it was permanently discontinued. Impeachment was used by the English parliamentarians to control the agents of the Crown and the powerful nobles who the ordinary criminal process was unable to discipline or punish. Impeachment was, therefore, a parliamentary mechanism for controlling the agents and favourites of the corrupt and dictatorial monarchy.

There were three essential features of the English system, namely, (1) it was specifically limited to criminal offences; (2) the prosecuting body was essentially different from the trial body; and (3) the trial body had a significant component of judicial officers and experienced lawyers.

With the expansion of the franchise in the 1830s and the growth of the principles of ministerial responsibility to Parliament as well as the increased effectiveness of the judicial system impeachment was no longer regarded as a necessary or desirable option. Thus, votes of censure became the accepted method of calling ministers to account for unethical behaviour and prosecution in the ordinary courts the preferred avenue for dealing with the commission of criminal offences by parliamentarians. After the controversial Lord Melville’s impeachment and his acquittal in 1805, there was no further resort to this system.

At the independence of the United States, impeachment was adopted at both the Federal and State levels. Accordingly, it is the US example that has usually been followed by other countries. When the American Constitution-makers discussed the adoption of the impeachment process, there was intense debate as to whether impeachment should be extended beyond serious criminal offences. Secondly, the disparity and conflicting views of the States at that time did not expose the problem of the undesirability of the prosecuting house being similar in political composition and “passions” to the adjudicating house.

Accordingly, in the making of the US Federal Constitution, the founding fathers provided that the House of Representatives should formulate and present the charges to the Senate as they did not then envisage that both bodies would become subject to similar political biases. As it has since been demonstrated, the Senate has failed to satisfy any test of judicial competence, impartiality, or political independence.

NO ACTUAL ROLE

Although it is provided that the chief justice should preside, he has no actual role in the debate or decision-making. The result is that the American model has failed to achieve the objectives of fairness, judicial independence, or competence. It should be noted, however, that the Federal Constitution retained the strict limitation of impeachment offences to criminal offences. Thus Article 4(2) of the US Constitution limits impeachable offences to “treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors”.

In The Politics of Impeachment, edited by Margaret Tseng and written before the President Trump impeachment, the editor described the book as addressing the increased political nature of impeachment at both the national and state levels, highlighting the politics of initiating impeachment charges, the political and partisan nature of how the proceedings are conducted, and the political fallout afterwards. From this account, there can be no doubt that the American experience is a strong warning as to the low ethical levels to which impeachment proceedings are likely to descend in a politically partisan environment.

The most recent cases of impeachment in the United States concerned Donald Trump’s alleged attempts to corrupt the electoral process, overturn the presidential elections, and instigate a violent attack on the Capitol building. Once again, political factions prevailed. Although many prominent Republicans condemned Trump’s complicity in and condoning of the attack on the Capitol, the necessary two-thirds majority could not be obtained in the Senate, and he was acquitted.

Some Commonwealth countries in Eastern and Southern Africa have adopted an impeachment process that is specifically related to elected presidents who are granted immunity from criminal prosecution during their term in office. In general, this process is used specifically in relation to the abuse of presidential powers and not to the misconduct of parliamentarians generally.

This is, essentially, the approach taken in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, and Namibia. The experience of these countries is that the process involves national and international adverse publicity and heightened political tensions. It has also been a weapon in partisan political rivalry. These dangers would be greatly increased if the impeachment process is extended to all ministers and parliamentarians as well as to a variety of misconducts. These factors, in addition to the historical and comparative studies, are strongly against the adoption of a system of impeachment.

In the next article in this series, I will, against this background, examine the legislative proposals that have been made in Jamaica to introduce a system of impeachment and the extent to which those proposals solve or aggravate the potential problems.

Dr Lloyd Barnett is an attorney-at-law and author. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.