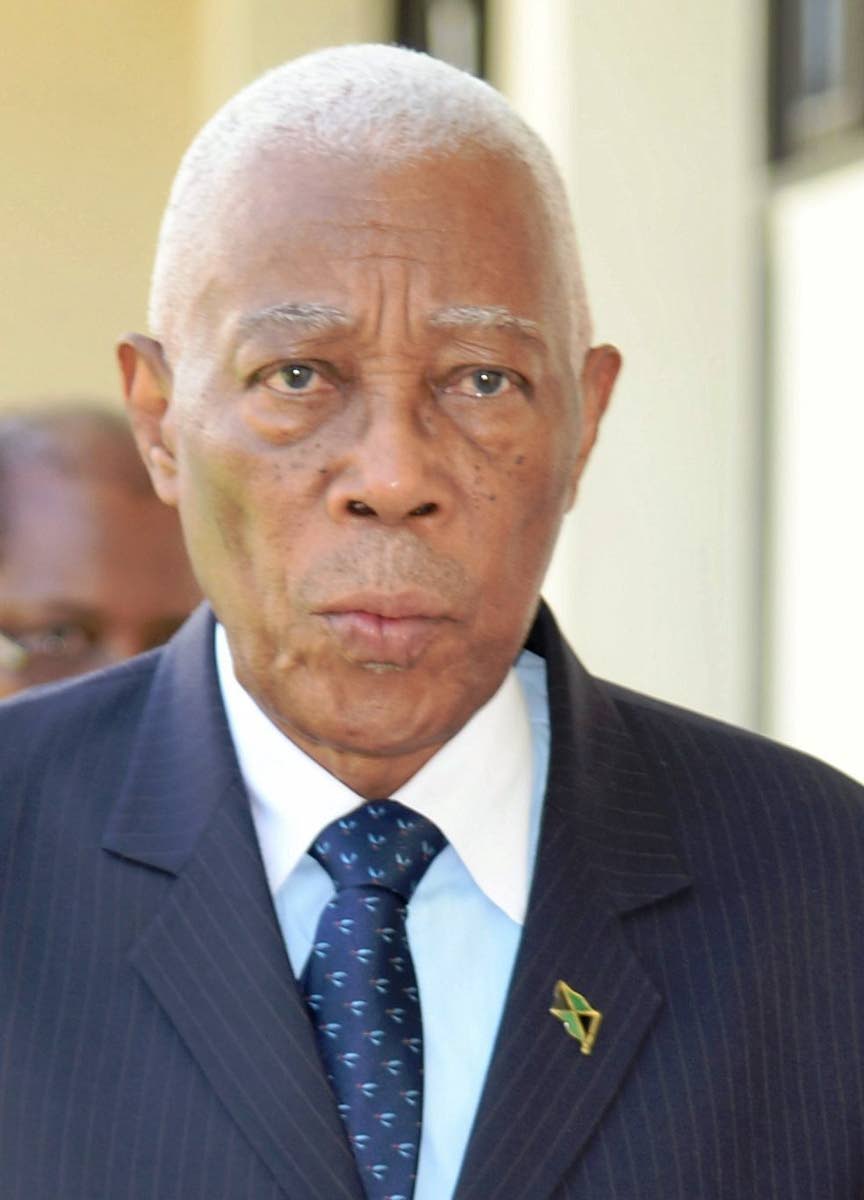

A.J. Nicholson | Fresh start advocated, Prime Minister

Loading article...

Prime Minister Holness’ decade-long silence concerning access to final justice ended in a pre-election debate in answering a question on Jamaica transitioning from the Privy Council to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ).

He projected proposals for a local final appellate court and for Jamaicans to be consulted, echoing his 2015 Sam Sharpe Square suggestion of a “grand referendum”.

Jamaicans were being notified of his Jamaica Labour Party’s (JLP) change from the position of a regional court, which a government of their own party had implanted into the national agenda over half a century ago in 1970.

Suggestions of a local final court and a referendum have long been debunked, with irrefutable reasons repeatedly placed in the public domain brushed aside by JLP leadership.

The prime minister’s proposals do not furnish a solution. They, unfortunately, strangle prospects for provision of access to final justice, a privilege enjoyed only by the wealthy.

His party recently received a fresh, sobering mandate, presenting an opportune moment for justifiable change to a “new vision” to move the reform process forward on a sustainable basis:

LOCAL FINAL COURT

The prime minister, unfathomably, presumes to overturn the long-settled position of a regional court upheld by six heads of government - three on either side - who preceded him: from Hugh Shearer to Bruce Golding.

It defies the parliamentary imprimatur of a recommendation in the 1995 Report of the David Coore-chaired Joint Select Committee on Constitutional and Electoral Reform, providing the catalyst for then Prime Minister P. J. Patterson to direct Jamaica’s participation in its creation.

It is assumed that his reference is not to Jamaica’s court of appeal with the process ending at a second tier, rarely encountered worldwide.

Yet multiple questions arise! Can it be substantiated that a local final court of a third tier is likely to gain global approval?

There is strong international competition for judges to serve on final appellate tribunals. Could Jamaica compete successfully in that arena?

Demonstrably, no assurance can be given concerning the prospects of economically challenged Jamaica, within any foreseeable time, establishing and maintaining a state-of- the-art final court that is uncompromisingly insulated from political and other influence.

It is acknowledged that the justice ministry occupies a poor cousin space within the national budgetary framework. Glaringly, are the Parish Courts not mostly of 19th- century vintage?

Nonetheless, should nationalistic fervour lead to a local final court being the remedy, the bona fides of the Government in their sworn commitment to serve the best interests, particularly of the disempowered, must be tested.

Until the possibility of the creation of such an institution eventuates, do they regard the company of our cousins in the region so loathsome that they allow access to final justice to continue as the privilege only of the wealthy?

In their reckoning, is embracing the accessible internationally acclaimed CCJ prohibited, even as an interim measure?

THE REFERENDUM DEMAND

Two piercing questions are normally posed by the impartial observer:

How does the JLP leadership rationalise joining with others to seek guidance from the Privy Council on the constitutional path for Jamaica to accede to the CCJ, and with the answer given, proceed to substitute their own requirement?

Then, on what proper democratic practice do they base expectation of support from the other political party and the Jamaican people to abandon the imperatives of the rule of law and the dictate of the Constitution declared by the highest court?

Such perplexing questions aside, a referendum proposal is absolutely the worst suggestion that can be advanced.

Not a single former colony has changed from the Privy Council to their accessible final court through the referendum route.

The judicious reasoning why all have feared, and opted not, to tread that path is well established.

A referendum is, essentially, a political exercise, and matters relating to the judicial system ought never to be exposed to the hustings.

Irreparable damage could be done to that sensitive branch of government from a platform anywhere.

Further, within the Westminster system of parliamentary government, referenda do not yield desirable or truthful outcomes. Whatever the question that is posed to the electorate, current political issues are inevitably injected into the campaign. Brexit surely comes to mind!

There are stark examples right here in the region. Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, and St Vincent and the Grenadines, exceptionally, have constitutional requirements of a referendum to exit the Privy Council.

All three territories have embarked upon the exercise, with similar results. Each campaign became consumed with political issues rather than on access to justice concerns, yielding unhelpful outcomes.

ACTIVATE A RETURN

Prime Minister Holness is earnestly exhorted to activate a return to the juncture where the Privy Council, answering his own party’s petition, directed a special parliamentary vote for transitioning to the CCJ.

At that juncture, consensus reigned, all moving forward in one accord!

From early along the Independence journey, there was philosophical reasoning why conquering lack of access has been an unchallenged priority.

The orthodoxy, the well-travelled road - unlike the Government’s unproductive pursuit - is that access to final justice takes precedence over withdrawing from the monarchy!

Lack of access to final justice has bedevilled every former British colony and has had to be rectified upon attainment of political independence.

No nation – not Canada, Australia, or New Zealand, for example – has ever seen themselves satisfied with final justice delivered by descendants of colonisers, even while maintaining a constitutional monarchical system.

For former Caribbean colonies, including Jamaica, pursuit of abandoning the symbolic monarchy pushes the decolonisation process.

Vitally, however, discarding delivery of final justice by descendants of enslavers is integral to the emancipation process from embedded mental slavery.

To empower the disadvantaged majority, Prime Minister, is there not the need of a fresh start – a clear new vision?

A.J. Nicholson is former minister of justice and attorney general of Jamaica. Send feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.