Editorial | Good governance agenda

When the new administration takes office after next week’s election, it must, along with economic issues, make good governance and efficient government urgent matters it attends to.

For not only do Jamaicans doubt the integrity of their leaders and key institutions of the state, the island has in recent times slipped or marked time on global indices ranking efficiency or decency in government.

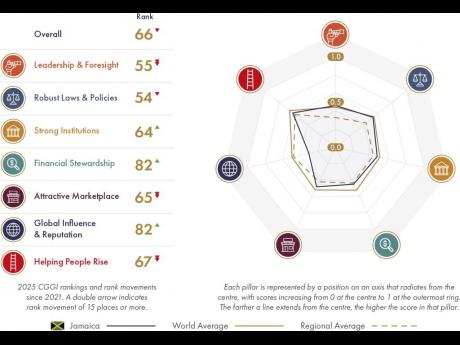

For instance, in this year’s Chandler Good Government Index (CGGI), the island is ranked at 66th of 120 countries, down two places on the previous year, albeit there was a small uptick in its score to reach 0.495, where on a scale zero (0) to one (1), the latter represents a country where critical systems of government operate at their optimum. In the 2021 index, Jamaica’s overall score was 0.504, which slipped afterwards.

The CGGI, which assesses the capabilities of governments, has been produced annually since 2021 by the Chandler Institute of Governance (CGI), a Singapore-based NGO, that was founded by Richard Chandler, a New Zealand-born billionaire investor and philanthropist, on the basis that good government and governance are key to a country’s long-term prosperity.

The CGGI is increasingly used by governments to compare the systems against peers, as well as by investors seeking to understand the environment of countries where they are considering putting capital.

COMPOSITE SCORE

The CGGI’s overall score is a composite of the scores of seven critical pillars, which are informed by 38 underlying indicators that measure how governments perform and the impact of their policies.

For instance, on the question of leadership and government foresight, Jamaica ranked 55th in the 2025 report, but was one place better (54th) on the robustness of its laws and declared policies. However, on the question of the strength of institutions, though, the island ranked 64th, one place better than its ranking as an attractive marketplace, which was 17 place better than its comparison with other countries for financial stewardship.

Surprisingly, on global influence and reputation, Jamaica ranked 82nd among the 120 countries, while on how the domestic environment and good government/government policies help citizens to rise, its rank was 67th.

Within these broad categories there were wide variations in the rankings on the indicators upon which they rest.

So on ethical leadership Jamaica was 54th among the 20 countries, in close proximity to its standing on the rule of law, the quality of its judiciary and transparency. However, it falls to 64th on regulatory governance, although its standing was 31st on quality of the bureaucracy, but 55th on property rights and 91st on logistics competence.

With respect the critical factors seemed critical in helping citizens to rise Jamaica was:

. 81st in eduction;

. 85th in healthcare;

. 116th in personal safety;

. 90th in income distribution;

. 60th on satisfaction with public services.

However, it ranked sixth on gender gap issues and 38th on the broader question non-discrimination.

OUTCOMES

The bottomline is that the CGGI attempts to measure how well governments function, and therefore focuses more directly on outcomes. Which is also impacted by the ethical and moral frameworks that governments set for themselves.

For example, it estimated that corruption nationally costs Jamaica between five and seven per cent of its GDP, which means large amounts of money end up in the pockets of individuals rather being spent on services, infrastructure or for the delivery of the goods for which it was intended. That negatively impacts economic growth and the country’s development. That partly explains Jamaica’s rank in the CGGI in the “help-people-to-rise” indicators, such as education, health and satisfaction with public services.

Citizens are not oblivious to these issues. While they appreciate that historic and structural and global factors contribute to these outcomes, they also perceive that they are deeply exacerbated not only by management weaknesses but often the deliberate contrivances of government and the public bureaucracy. In other worlds, people see a failure in governance.

This is reflected in part by the 86 per cent of Jamaicans who believe – as per Vanderbilt University’s LAPOP biennial report in 2023 on attitudes to democracy in the Americas – that corruption in public bureaucracy is deep in the island.

CORRUPTION

It also shows Jamaica’s ranking last year, among the 180 countries rated by Transparency International (TI) and the 73rd least corrupt country in the group, down four places from the year before. The island’s score of 44 on the TI’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) has remained static for several years.

Indeed, 50 per cent of Jamaicans, according to the LAPOP survey, said in 2023 they would back a military coup to fight corruption and while 58 per cent said they believed in democracy, only 28 per cent believed that, in Jamaica, it worked in their interest. The latter figure was down from 45 per cent two years earlier and 59 per cent in 2012.

These perceptions are likely to have been hardened by the assault against the island’s Integrity Commission (IC), the anti-corruption agency, by influential members of the government during the last Parliament, because of disaffection with aggression and subjects of some of its probes.

The bottom, therefore, is that the new government has not to mend fences with the IC, but to be absolutely clear about where it stands on good performative aspects and the philosophical underpinnings of governance. That place has to be intolerant of inefficiency and corruption.